My purpose is to give hope to those who have lost hope. Without hope, we remain lost in the Shadow Lands. |

****

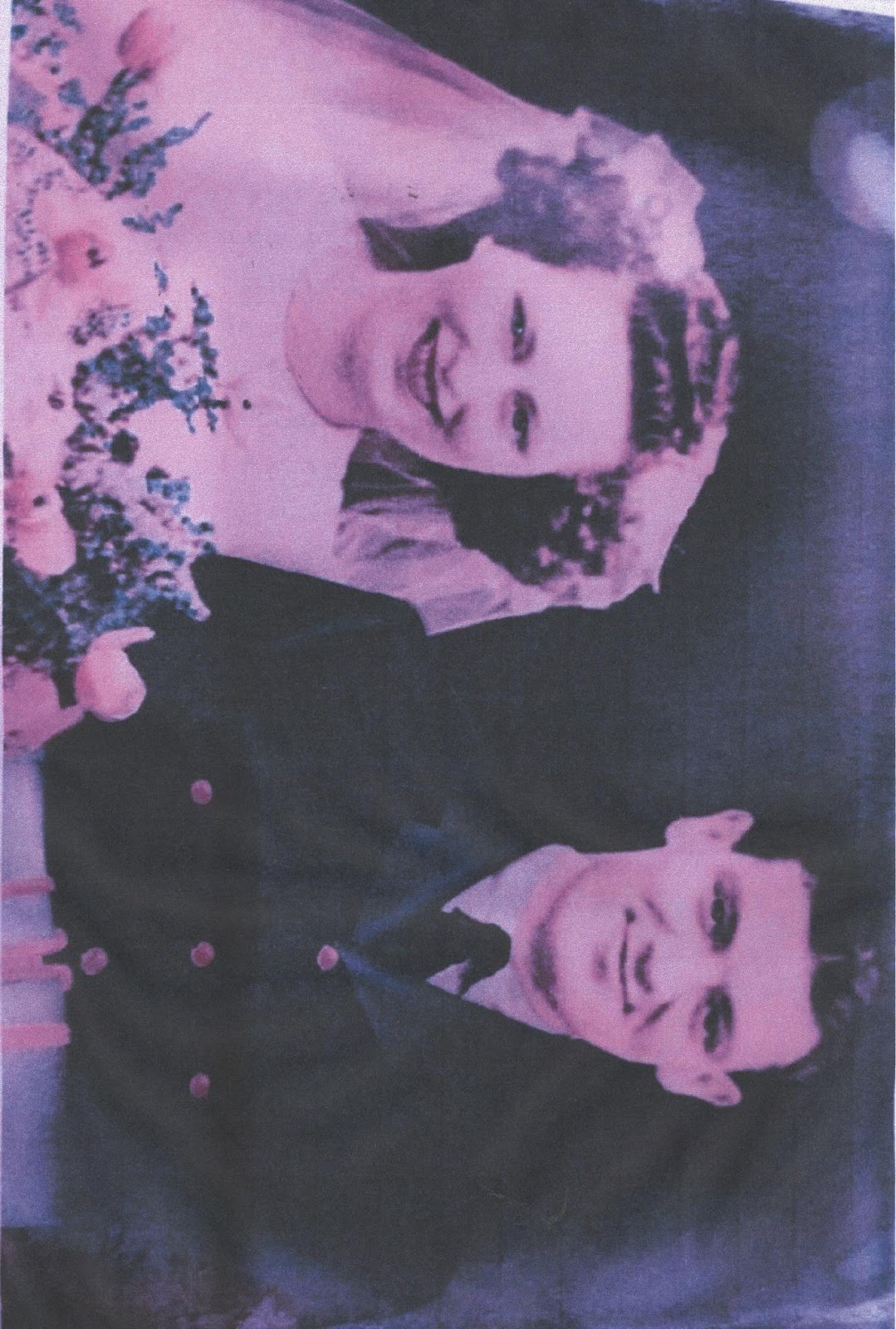

Cliff and Josephine on their wedding day 10th of March 1945. This photo once sat on a shelf in the lounge room at home. One of my siblings has the original and this is a copy. Cliff was still a serving member of Bomber Command in March 1945 and he wore his uniform when he married. In this photo, someone (one of my siblings) has removed Cliff’s RAF insignia from the sleeves of his jacket.

****

I have copied this photo from the funeral pamphlet produced by my siblings for Josephine’s funeral. I think this photo dates from the 1940s. Josephine looks so very young in this photo.

****

By the time this photo was taken, Josey was confined to a nursing home and the calendar said it was the 21st century. I doubt she was really aware of the presence of one of her grandchildren … but you never know.

****

It is relatively easy to imagine the dangers faced by the aircrew who opposed Hitler. Two popular songs from the 1940s brilliantly capture the remorseless horror and danger faced by aircrew. Here are the lyrics from Coming Home on a Wing and a Prayer.

COMIN' IN ON A WING AND A PRAYER

Comin' in on a wing and a prayer Comin' in on a wing and a prayer Though there's one motor gone We can still carry on Comin' in on a wing and a prayer

What a show, what a fight Yes we really hit our target for tonight

How we sing as we limp through the air Oh. Look below, there's our field over there With our full crew aboard And our trust in the Lord We're comin' in on a wing and a prayer

One of our planes was missing Two hours overdue One of our planes was missing With all its gallant crew The radio sets were humming They waited for a word Then a voice broke through the humming And this is what they heard:

Comin' in on a wing and a prayer Comin' in on a wing and a prayer Though there's one motor gone We can still carry on Comin' in on a wing and a prayer.

What a show, what a fight Yes we really hit our target for tonight

Now we sing as we limp through the air Oh. Look below, there's our field over there With our full crew aboard And our trust in the Lord We're comin' in on a wing and a prayer

Though there's one motor gone We can still carry on Comin' in on a wing and a prayer |

Look up the lyrics of Wish Me Luck As You Wave Me Goodbye. They should make you weep.

****

The dangers faced by RAF groundcrew are not well known.

****

One night when Cliff was very drunk, I asked what it was like being in the RAF. Cliff blurted out that once he saw a colleague walk backwards into a propeller. I didn’t have the heart to push him for more information. This was definitely a conversation stopper. I know this happened because it was confirmed by Cliff’s brother Eric.

****

The slang word for a groundcrew Aircraftman was “Erk” – and Cliff was an Erk.

Erks worked incredibly long hours and their work was extremely dangerous.

Life as an RAF aircraftman during WWII was one of pressure, long hours and hardship, as the operational effectiveness of the entire Squadron and their ability to fight was squarely on their shoulders. It is true to say that if you were posted to one of the many RAF Maintenance Units around the country, you could expect to work more regular hours, but if you were assigned to an operational Squadron, things could be very different and it is difficult to imagine how they managed to retain morale and general well-being. For ground crews assigned to bomber Squadrons on night operations, the working day would start early in the morning with the Daily Inspection. The crew that had flown the aircraft on the last operation would come down to the bomber and discuss with the ground crew any issues that they experienced with either the aircraft, equipment, or engines during the mission. Anything highlighted as a problem was noted on a Form 700, which was colloquially referred to as a ‘snag sheet’, but was a significant document on an RAF airfield. As long as Form 700 was in the hands of the ground crew, that particular aircraft belonged to them and it was unavailable for operations – no one on the airfield could order an erk to sign off the aircraft, until he was happy that everything on the snag sheet had been rectified and checked. Once all the work had been completed and the captain of the aircraft was happy, he would be asked to sign the form and responsibility for the aircraft would pass back to him. |

****

Not only was the work of RAF ground crews during WWII long and arduous, it was also extremely dangerous and many aircraftmen lost their lives, or suffered serious injury in the execution of their duties. By its nature, an operational airfield is a hazardous environment at the best of times, but during wartime conditions and working under extreme pressure, the possibility of accidents and injuries was greatly increased. Without looking at the hazards of working with highly flammable materials, or dealing with live explosives and ammunition, there was a more deadly peril – tiredness. Weary erks could quite easily walk into the path of a turning propeller, or simply fall off the wing of the Lancaster they were working on! The work of an RAF aircraftman was difficult and required great attention to detail – the lives of a great many airmen depended on their professionalism. The pressures under which they were required to work dictated that fatigue was a constant problem and it really is difficult to imagine how they managed to keep going. Most days brought the latest, highly pressured deadline, with a line of aircraft that needed to be prepared for the next mission and the option of missing the deadline simply not being an option. |

****

Cliff’s Service Record says that he was absent from duty without permission from 0800 on the 11th of November 1944 to 0830 on the 12th of November 1944. The Service Record also says that on 13 November 1944, Cliff was confined to camp for 10 days.

I have not been able to identify the name of Cliff’s colleague who walked backwards into the propeller and died, but I am certain that this incident took place just before 8.00 am on Saturday the 11th of November 1944. I have considered the possibility that Cliff simply got drunk on Remembrance Day 1944 and was unable to work because of this, but I discount this as absurd. Cliff never ignored moral obligations and keeping “his” planes flying was a deep moral obligation.

If Cliff stopped work on Saturday the 11th of November 1944, it was because something much greater than mere physical exhaustion prevented him from continuing to work.

Because he stopped working at 8.00 am on 11 November and stayed away from work until 8.30 am on Sunday the 12th of November 1944, Cliff was “confined to camp” for 10 days after the 12th.

I think it likely the days’ camp confinement was the RAF way of giving him some “time out” to try and recover from the shock of watching his colleague die in front of him.

****

By helping others to heal We help ourselves heal Remember those who preceded us. Give abundant Love Always Cliff always did. |

Comments

Post a Comment